The stories we tell ourselves, the stories we are told, and those too often untold: My conversation with Hollay Ghadery about her memoir “Fuse”

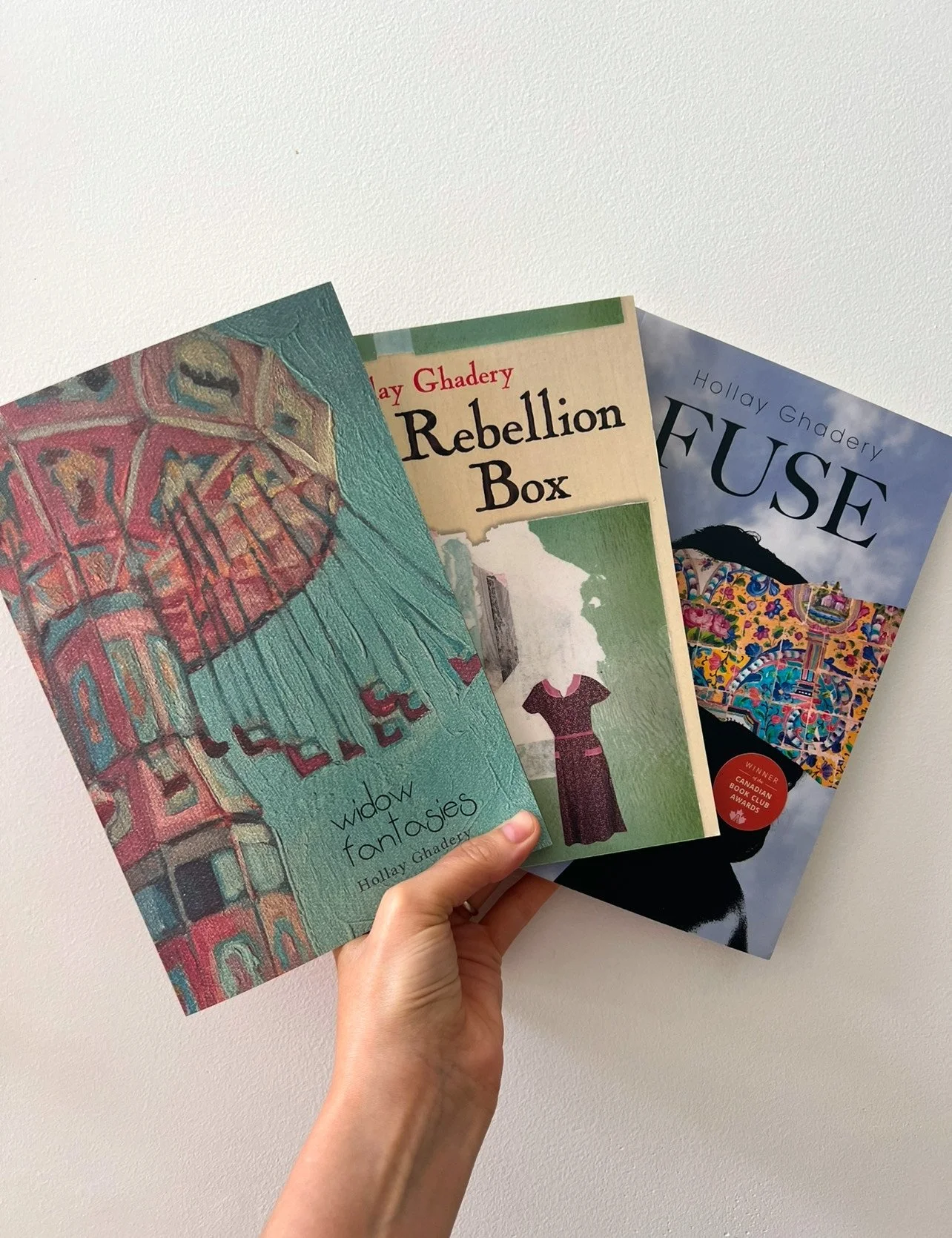

We met with Hollay Ghadery, the author of several books including her memoir Fuse, the short story collection Widow Fantasies, and the poetry collection Rebellion Box. In this first part of the conversation, we spoke with Ghadery to learn about the path from writing to publication, her dedication to radical honesty, and how the book was shaped with the help of editors.

What's the Idea: Thank you for meeting today to talk about your three amazing books. We’ll mainly focus on your memoir, Fuse.

Hollay Ghadery: Thank you so much for having me. I'm so flattered that anyone ever wants to talk to me about my books.

What's the Idea: How did you start the process of writing and publishing these books?

Hollay: Fuse was the first one that was published. That was a memoir. I've always considered myself a poet first, so it was a surprise to me that I went with that. That book is an exploration of mental illness. More specifically, it explores the way that biracial, or mixed race, women have a documented prevalence of mental illness, particularly eating disorders. Everything else kind of branches out from there. But I think all of the books start with just a little seed of rage. I know it's not good to be angry all the time, but I think that if you live in this world and you aren't angry all the time, then you're not paying attention to what's going on. They start with me thinking I can't be quiet about this. I felt called to write about the injustices that I saw in the world, but they're dressed up as stories. And even Fuse, which is a memoir, is still a story. They're stories that I tell people about my life as I remember them.

Pictured above are Ghadery’s three published books as of 2025: Widow Fantasies (2024), Rebellion Box (2023), and Fuse (2021). Although Ghadery always believed herself to be a poet first and foremost, she published her memoir first.

The poems are a little bit different, but they're still exploring issues of social justice and feminism, motherhood and the patriarchy, internalized misogyny and sexual violence, and even being biracial. And then, the short stories in my book Widow Fantasies use fantasies as a way to subvert the patriarchy and explores the way that people, women specifically, use fantasies to escape the oppression in our everyday lives.

So everything is coming from a woman-centered place of rage. But I would also argue that it's a very human-centered place of rage. I think you should be angry. I think that anyone with a shred of empathy would just feel angry about these same things regardless of whether you're a woman [or not].

What's the Idea: Taking that rage and processing it through writing, through art, is more productive and healthier than a lot of other options.

Hollay: I want to be clear that I'm not angry when I write. But this art is an expression of my rage and frustration and sadness with the world. Because I think for me, rage embodies not just this fiery, blindly angry feeling. Rage carries with it more than just anger because I'm not just angry. I'm sad and I'm frustrated because I love this world too much and I love people too much for this to be happening. I don't think my work necessarily comes off as the angry rantings of a bitter middle-aged woman. I hope all the multitudes we can contain are conveyed.

What's the Idea: Was there a particular idea that drove you to write Fuse?

Hollay: It started with having a kid. I have four kids. My eldest started asking me questions about scars on my body, which I recount in the book. I had self harmed for so many years, and I made up this story about a caterpillar because one of my scars looks like a big fat caterpillar has imprinted on my arm. I was telling him this story about this caterpillar because he was so young, about three or four, when he was asking me. How do you tell your kid “I sliced my arm open and had to go get it stitched up because I sliced it too much and I could see bone and it was gushing blood and it was a mess”? You don't. Not at that age. I could have given him a story besides a fairy tale, but I was trying to protect him.

Then it was time for me to start coming clean and stop telling these stories that had no basis in reality. And I started to think about the stories I've told myself growing up so I could live with myself. I started to think about the stories my parents told me growing up and how we all tell stories to make sense of our lives and be able to live with ourselves, and when do these stories help us? When do they hurt us? How much are they rooted in truth? Whose truth? That’s where Fuse began for me.

What's the Idea: How did you go about writing the book?

Hollay: My MFA [Master’s of Fine Arts] thesis was a terrible novella called Jump Track. I was trying to fictionalize this experience of somebody being an alcoholic, because I am, and having issues with her parents. But it was really dressed up as something different because I didn't want to deal with my life directly. I'd taken creative nonfiction courses in my MFA and I was kind of getting drawn to that. I wrote “Fuse,” the early version of the title essay, in Janice Kulyk Keefer’s creative nonfiction class. She was very encouraging. I was working on it thinking it would just be a standalone piece, and then I got very positive responses from readers. I never had it published on its own, but I felt moved to keep writing more and more and more and then eventually I was like, hey, I have five essays. Maybe I should just keep going with this theme.

“One of my reviewers said that Fuse was a hymn to family. I’m like, that’s it. I tried to deal with my parents and my brothers with the same compassion that I would want my children to deal with me and their own siblings.”

What's the Idea: Was it important for you to share these stories with your family? The book is very focused on your dynamics with your father, your brothers, your kids, your husband, and so on.

Hollay: No. Actually, my family reading it is something that would have stopped me if I thought about it too much. I was counting on my family not reading it. I was very careful to never speak to their motivations behind anything. I was only talking about what was going on with me. One of my reviewers said that Fuse was a hymn to family. I'm like, that's it. I tried to deal with my parents and my brothers with the same compassion that I would want my children to deal with me and their own siblings.

I consider Fuse very much a time capsule of the way I understood myself at the time. It's not like I disagree with anything that I said, but my thinking evolved a little. I don't even want to say evolved. I don't discuss this in the book, but there's a whole section of Iranians and non-Iranians that consider Iranians to be the “original Aryan race,” which would make me not biracial. So when this book came out, I didn't have it happen often, but every now and then I'd get somebody being like, "How are you biracial? Iranians are white."

Many wonderful books, including The Limits of Whiteness by Neda Maghbouleh, have examined the lived experience of Iranian people in America up against this myth. Things may have changed now, but in the United States, for Middle Eastern people, there was no box to click or check on the census. You just had to check white because there was nothing else. But none of these people had a lived experience of being treated like they were white. So if I was to write this now, I'd probably have something to say about that. I probably wouldn't necessarily call myself biracial as much as I did. And I wouldn't say I'm “half that,” because it reinforces a notion that I have of myself that I'm not enough, that I'm fractioned. Although I probably wouldn't use that terminology now, I understand why I used it at the time.

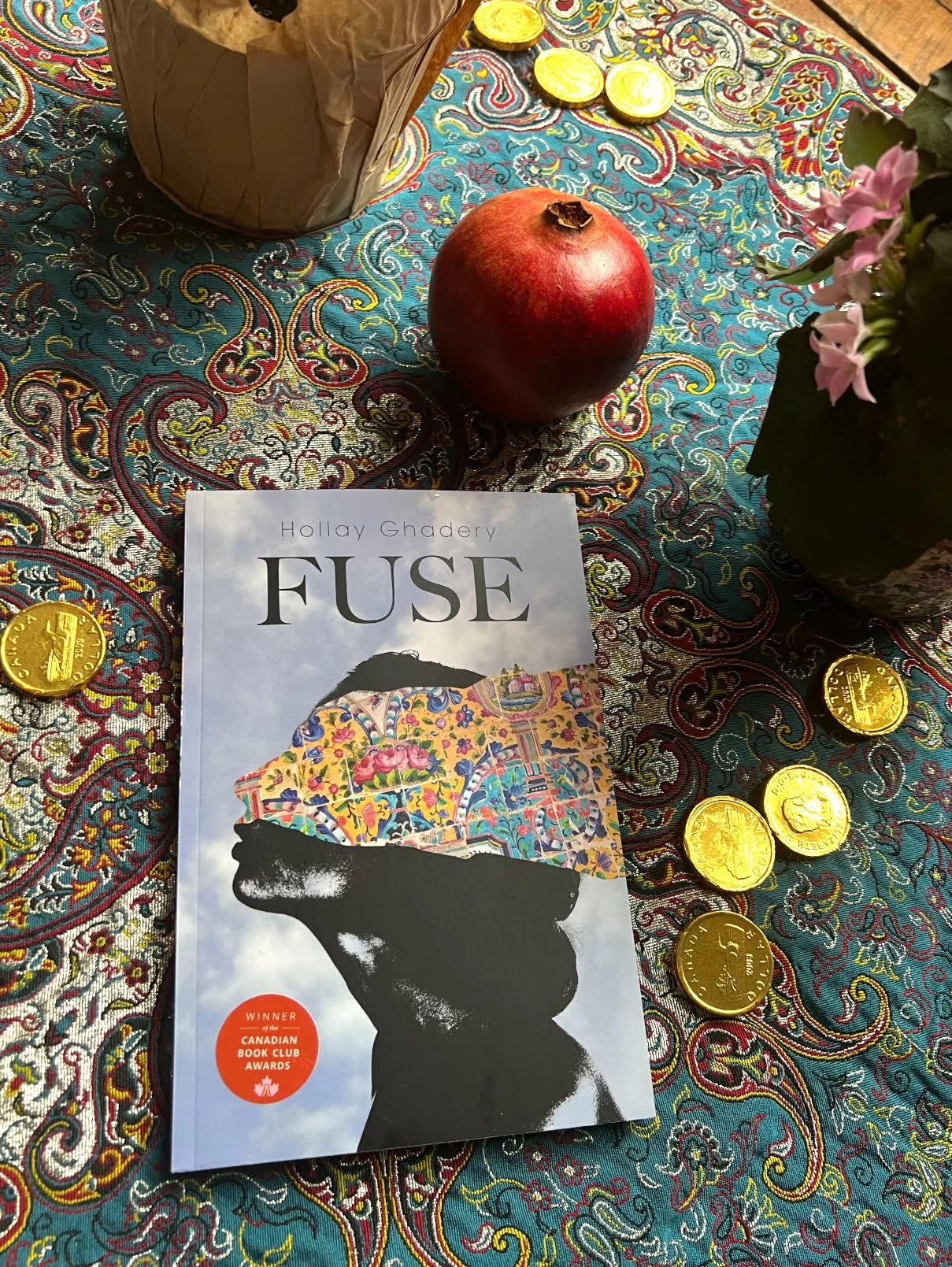

Fuse (2021) won the 2023 Canadian Bookclub Award for Nonfiction/Memoir. The book “explores the way that biracial, or mixed race, women have a documented prevalence of mental illness, particularly eating disorders.”

Like I said, I would never be able to write this again or write about things like going to a brothel now. I was very newly sober when I wrote this and everything was raw. It wasn't cathartic, though. When I turned to write this, I'd been through my Master’s. I understood I was trying to create art. I was trying to create a book by picking and choosing which parts of my life I was going to share. And whatever I shared, I was going to share one hundred percent honestly.

There’s stuff I did share that I'm like, my god, I can't believe I shared that. It's not shame. It's just like a different person who made this incredibly ballsy decision, but I didn't register it as ballsy at the time. It was just absolutely necessary to tell the truth. I'm glad I wrote it when I wrote it because just as you cannot step in the same river twice, I would not have been able to step into this book twice the same way.

What's the Idea: It's such an honest piece of work, and it can be very difficult to be that vulnerable. Throughout the book, you aren’t judgemental and you share your experiences so openly so people can understand you better. That’s the real beauty of what good writing can do.

Hollay: I've had a thought that's kind of crystallized recently. It’s essentially to do with the responses to me being in even my daily life a chronic oversharer. For the most part, I don't even realize I'm doing it until somebody tells me. People don't necessarily say “you're oversharing” but they’ll say “I love how candid or how open you are.” It’s like, okay I know what you're saying. You're saying that I'm giving too much away.

But I truly don't believe in other people's sanctity. I don't believe in giving them peace of mind at the expense of my suffering or somebody else's suffering. I'm sorry if I make you uncomfortable. Tough shit. Other people can do whatever they want with their stories or their information. That's fine. But I'm not going to protect you from the stories I need to tell. And I'm not going to try to protect you from myself or censor myself to make anybody else more comfortable. I just simply do not believe in other people's sanctity anymore because being quiet about things and trying to keep my mouth shut and not bother people and not take up too much space actually almost killed me in the most literal sense. So, I'm not going to do it anymore.

I don't go out of my way to make people uncomfortable, but I want to have these conversations. Let's talk about misogyny in the medical field. Let's talk about how women's bodies are named after male doctors. It’s worth it for me because when you have these difficult conversations or you start talking about something someone else considers taboo or too sensitive and they don't respond, I just know that these aren't my people. Because as many times as you get people thinking, who is this batty broad? As many times as that happens, you'll turn around and meet a new friend. It's like they've been waiting their whole life for somebody just to uncover something in them. And that's a really lovely experience.

“If you want to have a nuanced conversation, do something else. Write an essay or write a blog post because then at least somebody has to read the entire thing and engage with the entire length of your complex thought to respond to it.”

What's the Idea: I struggle with being reserved with my story and sharing my more personal opinions, so it’s awesome to see your confidence in speaking your truth. There’s a selfishness in withholding your story that is the opposite of putting yourself out there and sharing.

Hollay: I do think that the medium is the message. When Fuse came out, I would talk a lot about mental illness and living with mental illness on Instagram and on Facebook. I actually stopped doing that because I felt like social media while you're sitting at your kids swimming lesson or whatever you're doing is not the time for nuanced conversations like this. In my case, I was talking about living with an eating disorder in 2022 on Instagram and I got reported because somebody thought I was encouraging eating disorders, which is of course the complete opposite of what I spend my life doing. But because the algorithm or the people or the system policing this doesn't understand nuance, I got reported. Ultimately, who cares? But it was a little bit of a check for me to share my messages in places where they're suited. If you want to have a nuanced conversation, do something else. Write an essay or write a blog post because then at least somebody has to read the entire thing and engage with the entire length of your complex thought to respond to it. I feel like on social media, people are not reading everything. They are scrolling on by, engaging fast and fleetingly.

What's the Idea: As the writer, you can think about your message and be thoughtful, but as the recipient, your post is going to be one of a thousand messages they're going to see today. And some commenters are just trolls that are going to comment on a thousand messages and rage a thousand people for no good reason.

Hollay: And I'm not the kind of person who can just ignore it, unfortunately. My children have an account called Climate Kids because we're very big on climate activism and we share a lot of things. I monitor the account now because it just got out of control. We'll post about being outside in our pollinator garden or something, and I'm not interested in arguing with people who don't believe in climate change. They're not on this platform to listen or they're not there in good faith. I don't have the energy for it. But Fuse, of course, was something completely different because I could deal with this from multiple angles. I could deal with it in a nuanced manner. And if people wanted to argue with me, at least they had to buy my book before they could.

What's the Idea: How long did it take you to write Fuse?

Ghadery’s dedication to writing and stories extends well beyond her own writing. She is also a publicist, a co-host of HOWL on CIUT 89.5 FM, and a host on The New Books Network.

Hollay: I think Fuse took me over 10 years to write because it had so many incarnations and I wasn't sober. I think there's this myth that using drugs or drinking alcohol makes you more creative. At least for me, it did not. I wrote a lot of garbage and a lot of very false starts to this project while I was using because I was consumed by the addiction and the only thing I was interested in living in service of was this drug and making that lizard addict brain happy. So it wasn't useful for me. When I got sober, I wrote it very quickly. I think I finished it in two years after I got sober.

What's the Idea: Does the final book use any of the material from when you weren’t sober?

Hollay: I think there may have been tiny parts that were from when I was using. There's a scene where I'm talking about going to a beach with my ex-boyfriend and talking about a lake and feeling like crap in what I was wearing. I was not sober when I wrote that, but when I edited it and made it coherent, I think it turned out better.

What's the Idea: Did the book turn out like you wanted it to?

Hollay: It did but that's because I had wonderful editors. I don't think we can sing the praises of editors enough. They helped me shape it by being lovingly ruthless with questions like why are you doing this? I can remember an entire chapter or an entire essay just being highlighted by one editor and in the comment, it just said, “So what?” It was like ouch but also you're right. This isn’t adding anything so why the hell is it here? So I just scrapped that entire part and put it aside. I think I Frankensteined pieces I liked into short stories later on.

What's the Idea: It's good that you took that feedback well.

Hollay: I usually always take suggestions. Even if I end up not using them, I make myself defend my choice to myself. I try taking myself down, like, why is this important? There’s a scene in my novel that I'm editing right now where the editor's like, “I'm not loving this scene. Why is it here?” And then I explained in the comment why it was there. But as I was explaining it, I knew that I loved the scene because it's so absurd. I actually wanted it there mostly because I really wanted a sex scene in this book. The book is narrated by a sock puppet in the sex scene, so it adds to the absurdity of it. But as I'm explaining it, I'm like, my editor may be right. As much as I love it, and as absurd as it is, is it actually doing anything? I don't know. This is a discussion I'm going to need to have with her, but it occurred to me that I might just need to let this go, as much as I love it. I just really want to talk to her about it. That's what good editors are there for.

What's the Idea: If you do end up cutting it, there will be another time for your sock puppet sex scene down the line for the right project.

Hollay: There will be. I know it.

“I could not conceive of doing a chronological story because to me I haven’t experienced these things in any chronological order... And when I think of one experience in my life, it’s informed by and bleeds into other experiences and I can’t pull them apart. But there’s a commonality.”

What's the Idea: Were there any key changes that significantly shaped the final manuscript that you or an editor decided on?

Hollay: I think it was just making it flow naturally as possible considering that the book is not in chronological order at all.

What's the Idea: How did you kind of come up with the final structure?

Hollay: One hundred percent the editors because it's all in my head, it's my life, so I have no distance from any of it. It's thematically organized,, so thematically it's in order, but chronologically we're all over the place. I could not conceive of doing a chronological story because to me I haven't experienced these things in any chronological order. I don't feel what I feel chronologically. I feel everything at once sometimes. And when I think of one experience in my life, it's informed by and bleeds into other experiences and I can't pull them apart. But there's a commonality. The thing that's linking them all is the central argument I'm making or the thesis or the connecting force of each essay. And that made more sense to me and felt like that was more in tune with what I was attempting to convey.

What's the Idea: How many editors did you work with?

Hollay: I worked with at least three editors. One was before publication when I was in talks about the book with an agent who was really sweet and really lovely and ultimately couldn't take the book. When she first read it, she said to me, “I'm interested in this. I'd like to set you up with this highly recommended editor. Do you want to work with her?” And I was like, "Absolutely.” I had some grant money for it from the Ontario Arts Council. I would have had to find the money myself, but I didn't because I did happen to have this grant. So, I paid for an editor and she helped. She was incredible.

There was an editor I worked with on one of those essays because it was accepted. So while I was editing and it had been accepted to go to the agent but it still hadn’t been accepted anywhere, one of the essays in the collection got accepted for publication. I worked with an editor there on that piece, and I was so impressed with what she did with this one essay that when I eventually realized I wouldn't be signing with this agent and I was kind of on my own, I asked her to do the entire book. I paid her as well, just to see if there was anything else. She was helpful. And then there was the editor I worked with at the publisher when it was accepted.

What's the Idea: What did you learn from finishing the book and getting it published? How did you feel?

Hollay: I was happy to be sober. I learned not to wait for inspiration. Just sit your butt down and write. And it doesn't have to be fun. There will never be a right moment. Creating art is work. It's joyous work, but it's work. I will never romanticize the process again, which is probably how I've managed to complete other books since then. It wasn’t going to take me 10 years again because I've learned. I've lifted the hood, I've gone behind the curtain, I've seen what's there. And once I could confront that it's just your own laziness and apathy, I was like, "Okay, it's just up to me then."

What's the Idea: Do you have a set writing routine or writing schedule?

Hollay: Not at all. I do it when I can, but again, I don't romanticize it. I'm also writing poetry, and poetry is a very chill form. My poetry book that was published two years after Fuse had poems that were almost 20 years old that made it into it. So it's not like I wrote it all very quickly. I just finished it quickly. More than half of the poems already existed. But I feel like you can't rush poetry. I wrote my short story collection and my novel both in under a year. I have no problem rushing prose, but I don't feel like you can rush poetry. I feel like it's going to be ready when it's going to be ready. I just finished writing a poem that took me 20 years to write and I think the poem's like a page and a half. With poetry, it’s like I'm trying to access something that hasn't clicked yet. So I think it's good to do writing exercises a lot with poetry, whether or not those are ever going to be a poem.

What's the Idea: Congratulations on finishing that poem after 20 years. How do you know it's done? What makes it done?

Hollay: Even when I finally started to realize I was on to it, that I had the structure, it still took me two weeks to kind of work with it. I massaged it into what I needed. Why I think it's done is because when I read it, I feel what I want to feel. I feel the feeling that I have carried around in my stomach since 1985, which is when the poem is placed. I feel that it is there on the page. I'm sure there's still little line edits I'll do, but I don't feel like I haven't got the basis of what I'm trying to do.

What's the Idea: Thanks so much for sharing the story of Fuse.

Hollay: Thank you.

Fuse is available for purchase directly from Guernica Editions as well as your local bookstore. Follow Hollay Ghadery on Instagram to stay up to date on her latest projects or contact her if you have any questions.

Our conversations discussing Widow Fantasies and Rebellion Box are coming soon.

The interview was recorded using Google Meet in May 2025.

Transcription edited by Matthew Long, with additional copy editing by Anthony Nijssen of ATP Editing.

All photos are the property of Hollay Ghadery.