The science of grief and birds: Carolyne Van Der Meer on her book “Birdology”

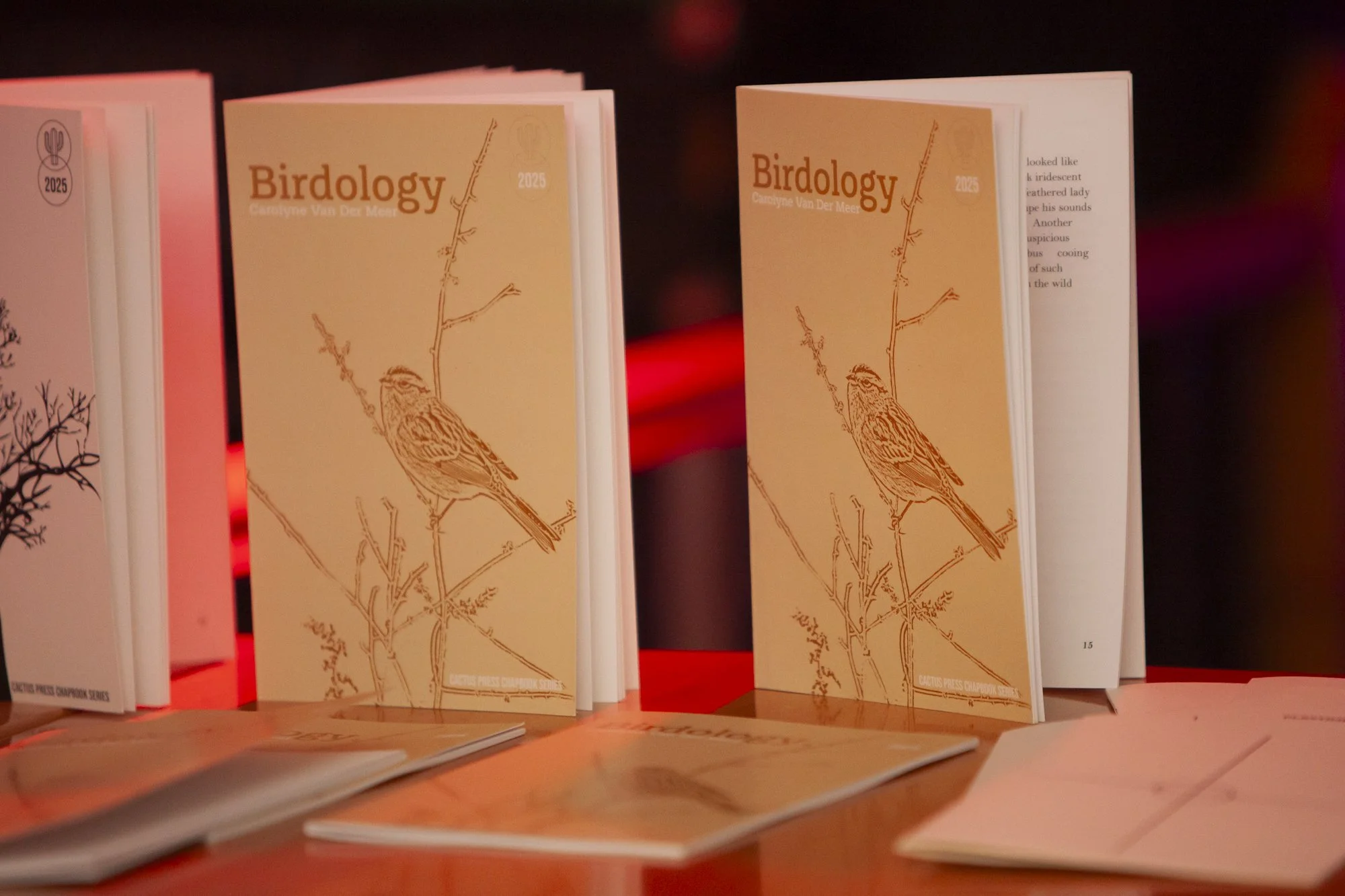

Carolyne Van Der Meer (pictured above) published her sixth book, Birdology, in 2025 with Cactus Press.

I met with poet, author, and journalist Carolyne Van Der Meer to discuss her chapbook Birdology (2025). We discuss how her original idea for the project evolved, the impact of grief on her work and how writing helped her process grief, and the benefits of publishing a chapbook.

What's the Idea: Thanks for agreeing to meet to talk about Birdology. What inspired you to write this book?

Carolyne Van Der Meer: First, let me thank you for having me! It’s always wonderful to be asked about what we write and why. And to talk about Birdology is a sheer delight for me. What's interesting about this little book is that it was accepted by the publisher, Cactus Press, two years before it actually came out. And I’m really grateful for that delay because it gave me time to figure out what this book was really about. Initially, it was a group of about twenty poems that all had some reference to birds—just me realizing there were birds everywhere in my work, but nothing really drawing them together. And then, my last couple of years have been so filled with grief and loss that I started to see that the birds were linked to this.

In 2023, my mother-in-law passed away from Alzheimer’s-related complications. I was very, very close to her. And then within less than a year, my father-in-law passed away—another great force in my life.

“The way it came together was a really nice process because I didn’t realize, in all of the other work that I’ve written, what a bonus time can be. We want to get the work out there, and there’s value in that, but sometimes it is good to sit on the work and realize that no, that’s not quite right.”

Over that period of time, I noticed a lot of my reflection on loss ended up somehow being intertwined with birds. I'd be sitting at the pier in my neighbourhood, and I'd feed the birds—and I'd be thinking about the process of loss.

And then, of course, there is my mom, who passed away in June. She had a collection of ceramic and wooden birds, her own fascination probably borne of the fact that her father had an aviary with many exotic and colourful birds. So, the birds have been a kind of punctuation. They've kind of been commas and periods and pauses.

I also took a nature writing class that grew into multiple subsequent classes with Chip Blake, who was the long-time editor of Orion, a nature magazine in the U.S. The first class I did with him was called What Birds Can Teach Us, and focused on just that. I thought, how coincidental that this has come up when I am trying to understand the bird motif in my work. I took it and then ended up taking three more classes over the next couple of years, classes that he had custom designed for the cohort from the first class.

He was mostly teaching writing the short essay and the nature essay. That wasn’t really my thing, as it's too long for me, but writing flash essays really appealed to me. So I wrote the flash essays that are in Birdology about my mother going into a care home and the loss of my parents-in-law. And then I decided, wow, wouldn't it be interesting to thread those into Birdology along with the poems. I could bookend the short essays with the poems and pick the right poems, not just any poem because it had a bird in it—but the poems that really spoke to the loss that I was going through. And I also switched out some poems for more recent ones.

The way it came together was a really nice process because I didn't realize, in all of the other work that I've written, what a bonus time can be. We want to get the work out there, and there's value in that, but sometimes it is good to sit on the work and realize that no, that's not quite right, but this over here is right. Is it really just that I want to talk about birds, or is it something much deeper than that?

Birdology started as a collection focusing on the reoccurring image of birds in Carolyne’s poetry before the shift focused to an exploration of grief and its connection with birds.

What's the Idea: I can't imagine the book without those pieces, Birdology I through V. They're so essential to the structure of the book and the feeling of it.

Carolyne: I think you're right, and I thank you for saying that. They felt like the reason for that little book to exist, so I was grateful that the publisher decided to delay publication because it helped me figure it out.

What's the Idea: Was the original collection all previously written unpublished material that had the theme of birds?

Carolyne: Some of it was old stuff that I kind of dug up. One of the poems, “Gratitude, Corner of La Gauchetière and Côté”, was published in my fourth book, Sensorial. It was the only one that I pulled from another place. In my latest book All This As I Stand By, there are a few bird poems that were written quite a long time ago, but for Birdology, I decided it made sense to include newer material, ones that really, like I said, spoke to the grief.

What's the Idea: Was the process of writing poetry, or writing in general, a way for you to deal with grief?

Carolyne: I think so. I've always seen poetry and writing as a way of processing. Maybe it's like that for you, too. I've learned through recent considerations about grief and poetry that it's a way for me to get it out. I think we sit with our grief over long periods, and sometimes we don't cry. We just hold it. The poetry was a way for me to let it go. And sometimes I've thought to myself, even most recently with my mom passing away, that I haven't cried much. Maybe it would be good to have a really good sob, but it doesn't always come easily. Sometimes I wonder if poetry is a kind of crying.

I think that if I had to define the word “birdology,” I would say it’s the science of grief and birds. It's a way of getting the grief out intentionally by truly sitting with it—in part by stopping and paying attention to the birds. I think when you go back to something you’ve written and reread it—or you read it aloud at a reading—you actually reprocess the grief. It's like a new way of getting it out again, which I think is actually very healthy.

There's also this idea that you write it and it's written in the throes of your grief—but once it's out, it becomes a piece of art. It becomes about the craft, right? And then you work on it, and you try to make it powerful, and you realize that this word isn't quite right, even though that's what you felt when you wrote it. But it becomes a piece of craft, and then you get to distance yourself from it. And I think that distancing is important because it allows you to hone the art of it, but it also gives you space from the grief.

What's the Idea: There are so many rounds of working with material throughout the process, from initially writing the book, then editing, to finally publishing it, and now being able to reflect back on it. Did it allow you to take a look at your grief differently?

Carolyne: Yes, it did. But the funny thing is that I find that I get very emotional with those “Birdology” pieces, especially the last one about my father-in-law actually leaving. I read them recently at a couple of readings, and I had to practice. And I don't always practice anymore. You do a lot of readings and then you just think, “I do this enough. I don't need to practice.” But I did need to practice them, because otherwise I was going to cry when I read them.

There was another poet who was launching her own chapbook that night. I’d heard her read before, and she would say, “I cry when I read so if I start crying, just roll with me,” and I thought that's a really great idea. But I didn't want to cry when I read those pieces. I felt like then I might not be able to continue. I guess that’s because I'm still grieving. I am still in it, especially for my mom, of course, because it's so recent.

Carolyne reads from Birdology in a live setting.

What's the Idea: I mean, it's so new, and it just takes so long.

Carolyne: So long.

What's the Idea: It's just a game of adaptation, unfortunately.

Carolyne: I am assuming then that you've lost people, too.

What's the Idea: I have, yeah, which was part of what made me connect with the power of these pieces, as well as the vulnerability of putting the grief state out there. Are you generally a very vulnerable open poet, or is this more the exception?

Carolyne: That's a really good question. I think that poetry is about vulnerability. It is vulnerability. But again, once you've written the work and you put it out there, it somehow makes you less vulnerable. Yes, you created it, and yes, it's a part of you, but there's a distance. So yes, I think my poetry can be very vulnerable, though I wouldn't call myself a confessional poet. I don't know if that's a trending word anymore, but it was for a long time, and it was something that was applied to women and was maybe a bit negative. I don't think there's anything wrong with being a confessional poet, but I don't think I always want to write about my feelings. I want to write about feelings, but they don't have to be mine.

But in Birdology, it was very personal. That was a bit of a departure for me from my more recent work. The book All This As I Stand By is a book about other people. It's more about asking questions like how do I tell the story of Marie Antoinette before she is beheaded so that it's powerful enough that the person who reads it actually feels like they're Marie Antoinette for a few minutes. That's what I was after with that book. And then to make the transition to Birdology, which was incredibly personal, was kind of scary for me. It's not to say that I haven't written personal stuff in the past. I have. But I think that my evolution as a writer has taken me away from that. I've actually kind of made a conscious decision to have the work be less about me and what I'm thinking and feeling and what I'm going through. It's more about how do I translate emotion? And then Birdology was just about my grief.

Did I enjoy that process? I think it was a necessary one. I'm super proud of this little book because I went into the heart of it. I didn't shy away from it.

What's the Idea: It’s just so human. Grief is one of the guaranteed things we all have to deal with.

Carolyne: It's universal, right? We all feel loss at some point. I took a lot of comfort in that when I wrote because I was like, okay, I'm going to put this out there, but there's not going to be a single person who reads it who's not going to know either the actual feeling of grief or the anticipation of it. We all imagine at some point or other, oh no, what's it going to be like when my mother's gone, or what would happen if my partner died tomorrow, God forbid? We all have those thoughts, face them, and then they happen in one form or another. We face anticipatory grief, and then we live it, so I felt good about Birdology being about a universal theme like grief.

A lot of people have told me that since they've read it, birds have come to them. Or that they'd see a bird after the death of a loved one, or they felt like they were communing with nature through birds when they'd lost someone. Or a red cardinal, the male cardinal, was the favorite species of their loved one, so every time they saw a red cardinal, they thought of that person. Birds are such a symbol—in literature and life—like sparrows being a sign of death coming.

Birds can mean many things to many people. Death, grief, but they can also symbolize hope. So it was kind of interesting that not only did people relate to the grief, they also related to the birds.

“One of the beauties of poetry for me is that I don’t know exactly what is going on in my head until I actually write it. And I know that if I wrote it at a different moment or in a different place, it would be a different poem. That poem came out of that moment that I was grieving my dad, but actually, it had nothing to do with him.”

What's the Idea: Was grief a theme originally when the first version of the book was compiled?

Carolyne: No, not really. The grief ultimately came out of those “Birdology” pieces. The only one I would say was written from a place of grief is the one I mentioned earlier, “Gratitude, Corner of de la Gauchetière and Côté.” I wrote that about my dad, though really, there isn't much truth to any of that poem. It's kind of interesting how the creative process can work. My father didn't have an aviary, but he was very kind to animals. That poem is an amalgamation of birds in my life. As I mentioned earlier, my mother's father had an aviary filled with exotic birds. He died when I was sixteen, so I didn't really get to research any of the birds that he would have had, but he was really interested in birds with colourful plumages. I remember as a very small child going to that aviary and seeing my grandfather interact with these birds.

When my dad passed away six years ago, I was walking and feeling sad, and I had this bread with me, and the pigeons just came at me. I was thinking about my dad, and I was thinking about how you just write things and you don't know where they're going to go. One of the beauties of poetry for me is that I don't know exactly what is going on in my head until I actually write it. And I know that if I wrote it at a different moment or in a different place, it would be a different poem. That poem came out of that moment that I was grieving my dad, but actually, it had nothing to do with him. It was just a way of invoking him.

A ring-bulled gull, one of the many birds common to cities close to bodies of water such as Montreal.

What's the Idea: You lost your grandfather with the aviary at sixteen. That's a pretty formative age. Did that impact you at the time?

Carolyne: It's interesting that you asked this question, but not because of the birds. It came up just this past weekend because of my mom's funeral. My husband said he had never realized that my grandmother passed away at such a young age. She was fifty-eight when she died of pancreatic cancer. So, he asked when my grandfather passed away, and I explained that he died when I was sixteen and on a student exchange in Mexico. I was there for something like six or seven weeks, and my mother phoned me. So I wouldn’t have said it was formative, but now that you’re asking me, yes, perhaps it was—because I remember so distinctly that my mother called me when I was in Guadalajara living with an exchange family, and she was so sad that her father had passed away.

But the birds themselves, I don't think I knew how to relate to them. My grandfather had an aviary, but also a barnyard with geese and chickens. The geese, of course, would chase us and honk at us and were always kind of aggressive. And so, I think I was a little put off by birds. But I do have a distinct memory of adopting a rooster from his farm when I was five. There are photos of me carrying him around with me—I called him Raggy.

But over time, I’ve become a little bit frightened of them. I really don't know how to behave with birds. I wish I did. Do you like them?

What's the Idea: I don't love birds. I do find some to be interesting, like eagles or other birds of prey, and some of the tropical birds are beautiful, and the fact they've been here forever is amazing. But I kind of see them as a part of another world. I don't fully interact with them.

“In the last few years, I’ve been listening more and stopping and paying attention. And I think that really does have something to do with grief, with losing people and kind of saying, okay, I need to slow down and listen. What am I not hearing?”

Carolyne: I totally hear you. It’s only in the last couple of years that I'm actually really paying attention. We're used to hearing birds chatter and whatever as we walk down the street. We hear that all the time, so we don't really pay attention to it. It's just part of the landscape, right?

In the last few years, I've been listening more and stopping and paying attention. And I think that really does have something to do with grief, with losing people and kind of saying, okay, I need to slow down and listen. What am I not hearing?

What's the Idea: It’s interesting you say that, because when I hear birds singing in the morning lately, I do try to stop and take it in and not take it for granted. There's our personal loss, but there’s also the ecological loss associated with climate change. We can't necessarily take bird songs for granted anymore.

Carolyne: I think you're right. Because I live in the city, all the birds I see are urban birds, and those are the birds in Birdology. Since my mom passed away, my husband and I have done a couple of nature walks at a local nature park called Cap-St-Jacques on the western part of the island of Montreal. We have spent a lot of time at this park over the years because we used to live nearby. But I never used to go there thinking that this was a good place to identify different birds. And on our more recent walks, I saw some birds that I'd never ever seen before.

I don't know if you've noticed this on your phone, somebody told me about it recently, but when you push the photo upwards to see the details of the picture, there's AI in there now that will tell you what you're looking at. And if the photo is clear enough, it will actually tell you the species of bird.

What's the Idea: That’s amazing.

Carolyne: Isn't it? I did take some photos. One was of a cedar waxwing. It's not a social bird, so you'll be lucky to see one. I happened to take a picture when we were walking, and when I looked later, my phone informed me it was a cedar waxwing. But all this to say that now I'm realizing that I can see other birds, not just the pigeons and the house sparrows and the seagulls and the red-winged blackbirds that are so territorial, and so common, downtown. There are other birds to see, and they're beautiful. Now I'm saying to myself, wow, look at all those colours. This is what my grandfather thought was so interesting.

What's the Idea: Thank you for sharing all that. That sounds like a wonderful response to grief and appreciation of life.

Carolyne: Thank you. That's a really nice thing to say.

What's the Idea: Why did you decide to make a chapbook?

The photo of a cedar waxwing taken by Carolyne at Cap-St-Jacques.

Carolyne: I'm a super huge chapbook fan, and I have always been. Chapbooks are, by definition, any poetry collection less than forty-eight pages. So once it's forty-eight pages, it becomes a full collection, and therefore the kind of thing your traditional publisher would publish. Chapbooks are typically published by chapbook presses or small presses, and there really are a lot of these publishers. I did a little feature with Hollay Ghadery about chapbooks where I list a few of the presses in Canada, and there are a good number of them that specialize in chapbooks alone.

It's kind of a special little niche for poets. Some of us see it as a place to publish before a full-length collection. And then there are other people, like me, who see it as a completely separate thing that is as valuable as a full-length collection. These little micro-presses are amazing. I had a great experience with Cactus Press, very personalized. This was a real engagement over questions like how do we make this book the best? What cover do you want? I had come across the work of a Toronto bird photographer, Priya Ramsingh, and loved her work so much, so I reached out to her to ask if we could use one of her photos. She sent me a few, and the publisher created a graphic treatment out of that.

So it was a very personal process. I loved that. But the other thing I like about chapbooks is that they don't take very long to publish. Birdology took two years, but that wasn’t the time it took to produce it. The actual production is quite fast. And a chapbook can take a variety of forms. Some are just stapled together with construction paper. So there's that sort of artisanal fun about them that they don't have to be anything fancy. In fact, some poets just produce them on their own. There are some publishers like Baseline Press in London, Ontario, that are all about artisanal paper, all about stitching it together. The books that Baseline produces are absolutely gorgeous.

There's also Gaspereau Press in Nova Scotia, which uses traditional hot metal typesetting machines. The paper is beautiful, and the cover stock is thicker, different from the interior stock. In a chapbook, these could easily be the same.

And also, if you're an emerging poet and you feel it's too early for you to submit, or you don't have enough work to submit as a full-length collection, you could submit to a chapbook press and get it out there earlier. It's a way to develop a portfolio. Let's say you're going to a literary festival and you want to be able to sell something, but you don't have a published book. You can put your chapbook together and sell it for an accessible price, and then your work's getting out there.

What's the Idea: People are willing to take a chance with a toonie or a five-dollar bill.

Carolyne: Exactly. And when you're at a literary festival, people will do that. They want to read new stuff, so it's a fast and fun way to get your work out there. And then, for the more established poets, it's great to have a different option—in the sense that you're not waiting. The thing about a traditional publisher is that the lead time can be long when you’re in the queue. For example, my book Sensorial was accepted in 2019, and it came out in 2022. It can take time.

What's the Idea: I love the brevity of chapbooks just because we're all busy. Your book was one of the rare books these days where I read the whole thing in one sitting. I loved being able to do that. And the conciseness of the format meant that there was no poem that didn’t fit with everything else. There was no filler just to get to a certain page count. Being able to concentrate on your theme creates great possibilities for writers.

Carolyne: It's so nice that you said that. I hadn't really thought about that before, but you're right. This was a truly themed collection, which I had not really ever done. I think that's a challenge for poets. When you're submitting a manuscript to a traditional publisher, you ask yourself these questions. Should I group the poems in a certain way so that it's obvious that there's a theme in part one, part two, part three, part four? Do I tell them how to think about it by how I organize it? There are varying points of view on that. Some publishers will say you shouldn't organize your work, it should be random, and then others think differently about that and want things to be sort of sectioned. But the nice thing with a chapbook is that you can do it and it's not going to overwhelm.

What's the Idea: Exactly. As we're all aging, we're going to be dealing with aging parents and other losses. I feel like Birdology could serve people as a companion through their grief in a similar way to how people use Joan Didion's The Year of Magical Thinking.

Carolyne: That's so nice. I hope for that, though obviously Joan Didion's book is in another class, and also so much easier to get than mine.

What's the Idea: Did the vulnerability of Birdology continue into your next writing?

Carolyne: I’m not sure, to be honest. Right now, the poetry that I'm writing is still a lot of processing of grief about my mom. My mom was a very, very powerful personality in all of our lives, a person of deep faith. Someone who was just so grounded with such strong values. I can't say enough good things about my mom. I'm still processing that. Like you said when we first started chatting, it will be a long time. So the work that I'm doing right now is a lot about that. Or that was the case leading up to her passing. I feel kind of silenced at the moment, like I don't have anything to say for now. Maybe my voice will come back, but I guess maybe I need to sit with my grief a while before I start writing again.

What's the Idea: I wish you the best through this healing process. Thank you so much for sharing.

Carolyne: You're welcome. And thank you again for spending time with me. I'm honoured.

Birdology is available from Cactus Press. Follow Carolyne Van Deer Meer on Instagram to learn more about upcoming events and new works.

If you enjoyed this interview, read more interviews from the What’s Your Idea series.

The interview was recorded using Google Meet in June 2025.

The interview transcript was edited by Matt Long of What’s the Idea Freelance Editing, with additional copy editing by Nikolai-Andre Alexander.

All photos are the property of Carolyne Van Deer Meer.