The journey of learning from the place where you live: In conversation with Daniel Coleman on the writing of his book “Grandfather of the Treaties” (part one)

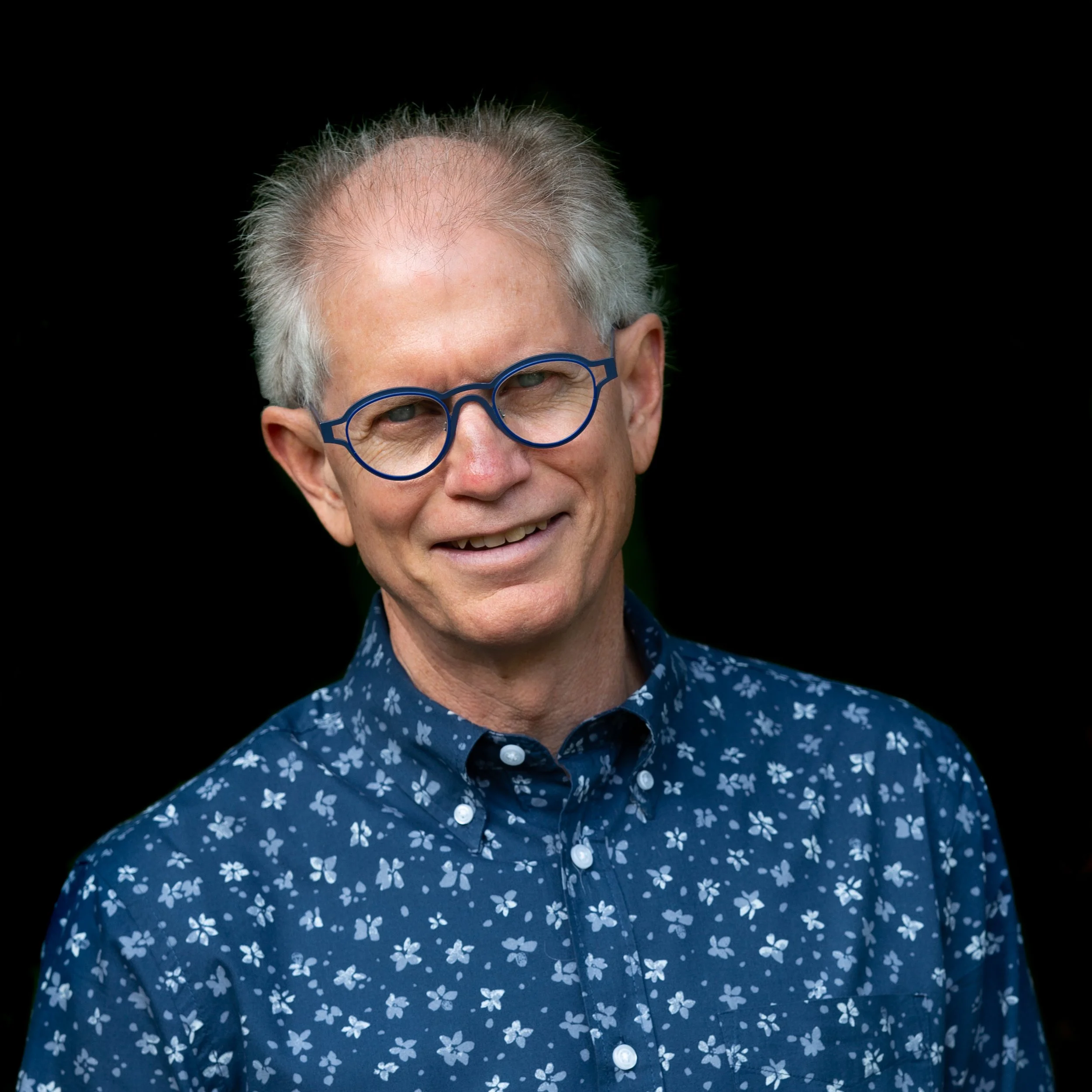

Daniel Coleman (pictured above) is an author and recently retired professor of English at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario. (Photo credit: Geoff Skirrow)

In part one of our conversation, Daniel Coleman and I discuss the inspiration and writing process for his book Grandfather of the Treaties. We cover Coleman’s journey to learning about Wampum treaties, the collaborative approach behind the book, and why these fundamental aspects of the original agreements between Indigenous Peoples and Europeans are only recently getting the attention they deserve.

What’s the Idea: What inspired you to write this book?

Daniel Coleman: I'd say that it's all part of my ongoing learning curve of understanding how to learn from the place where I live. I grew up in Ethiopia, the child of Canadians who worked there as missionaries all their lives. They would speak of Canada as home, and we kids — all of us kids were born there — would speak of Canada as home, too, even though it's a place where we'd never lived.

So, I grew up with a sense of belonging to a place that I didn't know anything about, and then wondering, well, what does “home” or “belonging” mean? There was also the question of place, and its importance in who you are, and how you become who you are, how you think like you do, all that kind of stuff. Maybe people who grew up in a country and stayed there, or lived there all their lives, wouldn't ask those questions, but because I was bounced around quite a bit in my youth, those questions were at the front of my mind.

When I came from doing my graduate studies to McMaster University for a job, I'd never lived here in Hamilton before. I didn't know this part of Canada at all. All I knew were the stereotypes that you see from the Skyway Bridge of the dark satanic steelmills. I moved here and then was blown away by the beauty of this place, and the green world that is Hamilton. The contradiction and conflict of this place showed itself right from the start. You know, the same place of incredible beauty and incredible abuse, and pollution, and disregard, and disrespect, and all that complexity. I found that fascinating.

Early in my time at McMaster, I met Haudenosaunee colleagues who said things like, “Books may be your teacher, yes,” — I'm an English professor, so books are a big deal — “but place is your teacher. The land is your teacher.” I thought, well, what does that mean? I had no idea what that meant. The effort to learn from the place became a book I wrote a few years ago called Yardwork. It's really about learning from the exact yard where I live, and the pine trees, the deer, the urban animals, and everything that lives here in the watershed.

And, of course, when you start paying attention to the place and the land, it gets you into Indigenous questions. What is the Indigenous history of this place? How did people live here before it got made into Hamilton as part of Canada, and the steel industry? Those things became fascinating to me.

Before 2006, I felt that respect for Indigenous knowledge, Indigenous people, and Indigenous ways meant that you stayed respectfully out of doing research in Indigenous communities, or writing about these things, because there's such a long history of people extracting Indigenous knowledge from Indigenous communities and using it for their own purposes, and telling Indigenous stories as if they were their own, kind of assimilating and wiping out Indigenous uniqueness by overtaking it in that sense. So I felt “respect” meant “keep out,” basically.

“At that time, Six Nations land defenders were saying, “Well, these kinds of conflicts occur because Canadians, non-Indigenous folks, don’t know the history of our treaties, and don’t know about the Two Row wampum.” And I thought, that’s true, I don’t.”

And then, in 2006, I came onto campus one day, and there were 30 police cars parked behind Mary Keyes Student Residence, and I thought, oh, it's April, students are going home for the summer and the police are using this residence for a conference, or some kind of gathering or something. Later in the day, I learned that McMaster was the barracks for the 200 armed police officers who raided the site at Douglas Creek Estates, known as Kanonhstaton, that was in dispute between Six Nations and developers at the time. The police roughed people up and arrested elders and youth during that raid.

During those days here in Hamilton, it was heated, the divide between Indigenous claims for land rights and their rights to land in relation to the settler state, to our Canadian nation. People were throwing rocks at one another and standing on barricades, and it was very heated, and it was a moment where I realized I'm not a spectator on the sidelines. I worked at a university that called in the police. We non-Indigenous Canadians are right in the middle of these relationships.

And at that time, Six Nations land defenders were saying, “Well, these kinds of conflicts occur because Canadians, non-Indigenous folks, don't know the history of our treaties, and don't know about the Two Row Wampum.” And I thought, that’s true, I don't. And it's my job to know those things, because I'm supposedly a teacher. If that's not even on the curriculum or the radar at a university where I teach, then we’re not doing our job.

So then that got me really into thinking, okay, “respect” doesn't mean “keep out.” It means trying to figure out how to do my part of the job without trying to overtake Indigenous knowledge, or make it my own. That effort to learn grew into this project.

What’s the Idea: How did you go about seeking out the knowledge that informed this book?

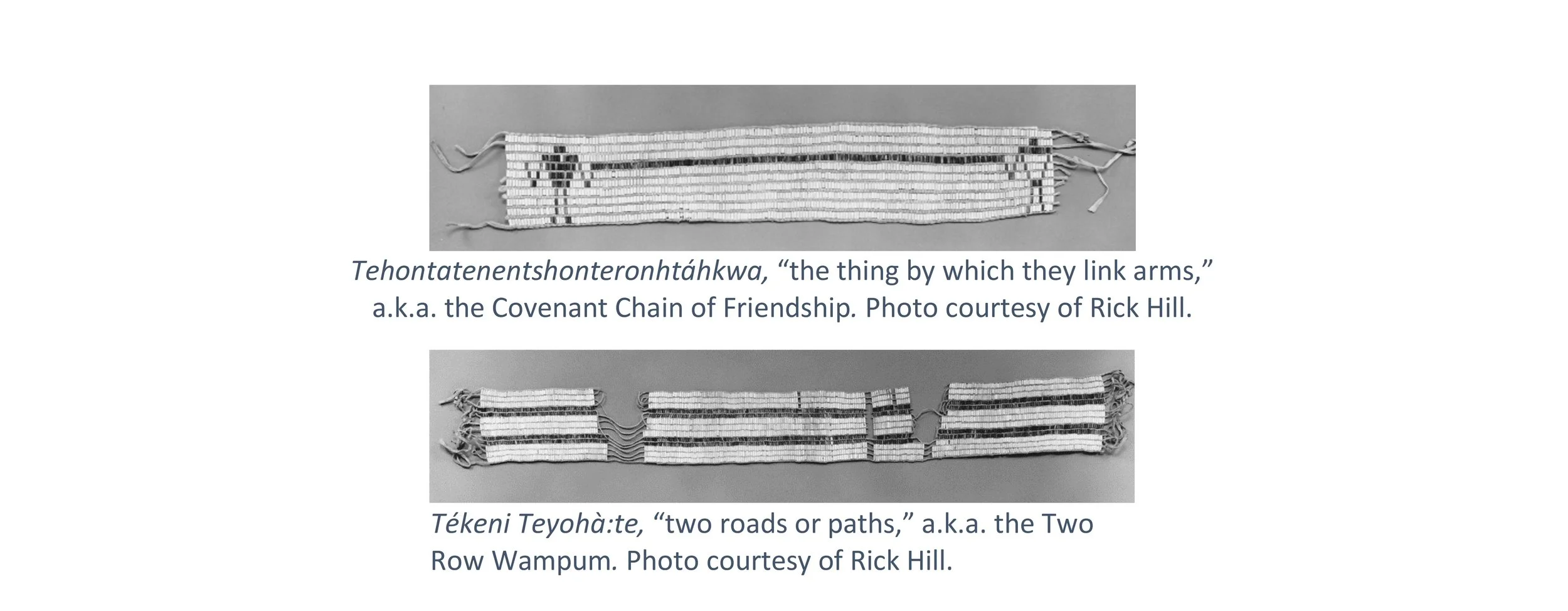

Daniel: I had invited Indigenous students and faculty to come and visit my classes to speak when I was teaching in my early days. People like Rick Monture, who taught with the Indigenous Studies Program at the time. He brought the Two Row Wampum and the Covenant Chain to my classes and talked about them. These are the first formalized agreements made between Indigenous North Americans and incoming Europeans back in the 17th century. The Two Row Wampum was an agreement made with early Dutch merchants who arrived on the Hudson River, and then when New Netherlands became New York, the Covenant Chain of Friendship was agreed upon with the British in 1667. These were agreements that the Haudenosaunee, who controlled navigation on the river systems at that time, made with these incoming merchants.

I had learned about these things from colleagues like Rick, and then because I was interested in such things, I was asked to be the academic co-chair for what was called the President's Committee on Indigenous Issues at McMaster. That had me out at Six Nations Reserve back in 2007 for a discussion about how a university could support Indigenous scholars living on the reserve in the creation of an Indigenous Knowledge Center based on Six Nations territory. We were consulting with some elders at the time, Ima Johnson, Lottie Keye, and Hubert Skye, and they said, “If you're going to establish this knowledge center, you should call it Deyohahá:ge:,” which in the Cayuga language means the Two Roads, or the Two Paths, which is a reference to the Two Row Wampum.

They were saying you'll need the best of Indigenous Haudenosaunee thinking, and the best of Western thinking to create this knowledge center, to create archives, and to keep track of these important Wampum agreements, historical artifacts, and language and cultural knowledge for the future of Haudenosaunee people. So that's why it needed to be based on the reserve, not at the university, and that anything we produced would be owned and managed by the Indigenous Run Centre called Deyohahá:ge:.

I've been involved with that Centre ever since. We've been holding Two Row gatherings because if the elders told us we were going to work with this idea of Deyohahá:ge:, the Two Rows, then we should have monthly gatherings to talk about the Two Row Wampum, what it means, and how we can live it out today. We've been meeting ever since, from 2007 to 2025, so 18 years of meeting every month and talking about these matters. It’s a small group composed of both Indigenous learners and researchers on the reserve and folks from surrounding universities.

These images (taken by Rick Hill) show the Wampums that served to record the the original established foundational relationships between the Europeans and the Indigenous Peoples of Turtle Island.

Out of those discussions, friendships have emerged from working together. Primary among them is Rick Hill, who is probably the world's leading expert in wampum studies. He's an artist and art historian of Tuscarora ancestry and he's been involved in wampum repatriation since the 1970s, a long time. He's published articles and done all kinds of work on wampum history, wampum meaning, wampum iconography, and so I've had a chance to work alongside Rick. We've published articles together, given lots and lots of talks together, produced some video material, and we co-hosted those Two Row gatherings over all these years.

At one point, we decided we've been talking for a long time, so we should put some of this material together. So, with Bonnie Freeman and Ki’en Debicki, Haudenosaunee members of that Two Row discussion group, we edited a book called Deyohahá:ge: Sharing the River of Life, the same title as the Knowledge Center, and we invited people who'd participated in these conversations over the years to write chapters. That book was published last year, and it's a collection of chapters by Six Nations writers and their neighbours. Sometimes partners wrote a chapter together. It's a powerful collection of essays on these topics of the Covenant Chain and the Two Row Wampum, and how they apply today. You could say that, in a way, that was part of my kind of on-the-ground and in-person research for writing Grandfather of the Treaties. And so, it grew out of those relationships.

I felt a strong sense of responsibility while writing this book, so it was a very collaborative process that produced this book. It didn't let me just kind of go off on my own and write whatever I came up with.

What’s the Idea: Were you regularly checking in throughout the writing process with your colleagues, or would you write and send over the material after?

Daniel: It was a mixture. Rick and I were working on similar things, so I was showing him chapters as they were emerging. And then another of the people who contributed to Deyohahá:ge: is a fantastic writer named Amber Meadow Adams. She's Mohawk, and an incredible writer, and I thought, I would love to get Amber's thoughts on this book as I'm writing it, so I worked out a contract with her to edit the book. She read it cover to cover, and gave me fierce, fierce criticism. That was a tough go because she's so demanding of herself, let alone me, as a writer and as a historian.

We had lots of exchanges. I would bring in chapters that I'd written as I was thinking about them and talk them over with the Two Row group. It was both consulting as it developed and then, also, when it was in its finishing stages. Rick, for example, made all the illustrations for the book.

He and I had planned to write this book together, but we wrote an article together, and that took us three years to cooperate that much, and Rick's getting up there in age, so I was saying to Rick, “You know, it took us three years to write an article. How long will it take us to write a book?”

And he said, “Okay, you write the book, and I'll make some illustrations and write the foreword,” which he did do, and I'm grateful for that. To make the illustrations, of course, he was reading the parts and giving me his comments on it, so it was very interactive all the way through.

What’s the Idea: Was there anything in the editing process with Amber Meadow Adams that was particularly important to improve the material?

“To understand these treaties: you need to understand them as an ecosystem of treaty-making, as an evolution whereby one treaty flows into and influences the next... These wampum treaties taught the British how to make treaties in the first place. They didn’t arrive on Turtle Island ready to sign treaties with Indigenous folks. They learned how to do that from these wampum agreements, and they flowed into and shaped one another.”

Daniel: With doing this kind of work, you can never know enough. I took an introductory Mohawk language class so I could just get my head inside the language concepts a little bit, but of course, all you learn is to introduce yourself and say a few words. So as I'm writing this book, these philosophical, ecological concepts that are part of these wampum traditions are embedded in Haudenosaunee language, and I don't speak that language. It would take a lifetime to learn the language fluently enough to be able to do this work to the max, plus there’s the challenge of needing to translate it into English and to convey these concepts… because in many ways, I'd say the book is about a different mindset that we Canadians need. We as people trained in Western culture and European thinking just haven't been raised to think that way. So it's a book that's, in some ways, as much a book of eco-philosophy and political philosophy as it is a story. The big challenge was to convey those philosophical concepts not in the language they were created in so that people who were raised in English and who speak English can understand them. And because of things like residential schools, most Indigenous folks don't speak those languages fluently anymore, either. So knowing how to convey the concepts of the wampum in English was a big challenge. Amber was really good for me with that. She would try to think, how do you say these things in a way that can convey their meaning to readers of English, that's still fair to the original?

We're operating in English because my audience is Canadians. I want people who don't know these histories to be introduced to them, and to learn how to think differently with them. As thorough and careful as I tried to be, and as Amber helped me to try to be, you can never get it totally right. It is a work of translation, and that's a tough job.

What’s the Idea: There’s an interesting passage about the importance of place and how it can influence cultures, influence your way of understanding, and how you can't just take one treaty or understanding and place it somewhere else, similar to language.

Daniel: The thing that you just said about treaties not being a thing you sign on a certain date and being contained by that single transaction, that's an important insight about these agreements and their kind of continual evolution. That comes from the work of Kayanesenh Paul Williams, who's a lawyer from Six Nations and for the Confederacy. He talks about how to understand these treaties: you need to understand them as an ecosystem of treaty-making, as an evolution whereby one treaty flows into and influences the next. And that's why my book is called Grandfather of the Treaties. These wampum treaties taught the British how to make treaties in the first place. They didn't arrive on Turtle Island ready to sign treaties with Indigenous folks. They learned how to do that from these wampum agreements, and they flowed into and shaped one another.

For example, a wampum agreement that I referred to in the book, but it's not on the cover of the book, is the Pledge of the Crown Wampum. I referred to it in particular because it was exchanged between the Haudenosaunee and the British right here in Hamilton at Burlington Heights. This was at the end of the War of 1812; the British and the Haudenosaunee had fought together as the Covenant Chain agreed to do, with linked arms as allies. After losing relatives on both sides of their alliance, they were hurting. There was a lot of suffering during the war, and so the British made this wampum called the Pledge of the Crown Wampum, and they gave it to the Haudenosaunee at Burlington Heights and said, “Thank you. We've been fighting together. We've protected our homes. And now it's time for you to go back to your reserve and your territory on the Grand River, and for us to go back to our families, and to take care of one another in this time of recovery after this time of violence and conflict.”

The other thing that's fascinating is that Europeans learned how to do this ceremony-and-treaty-making and saw its value. They didn't just say, okay, well, that's what you claim we said, we don't know what you're talking about. They made their own wampum and made their own replies.

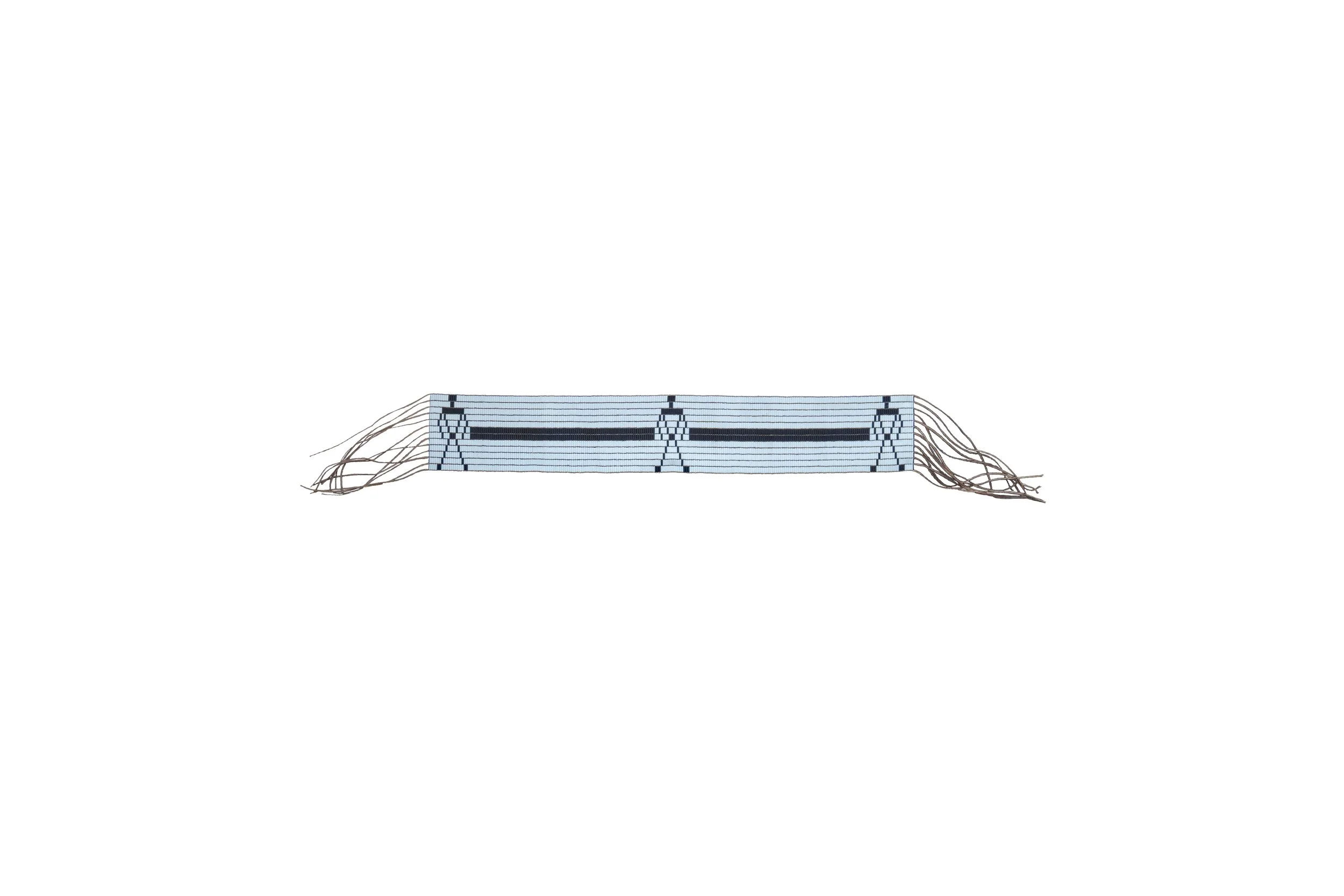

So, to bring that up to the present, there's a new wampum hanging at McMaster University. It was given to McMaster by Six Nations Polytechnic during the period when I've been working with the Deyohahá:ge:. It's like the Covenant Chain, but it has a third human figure in the middle of that rope that binds the two human figures at the two ends to one another . It represents the alliance between the university and Six Nations, and taking care of the student in between the learners of the future, basically the faces in the ground waiting to be born. This wampum was given to McMaster in 2014. So, you know, the wampum tradition isn't over; it's continuing to evolve, and I'm hoping that these books will give people a chance to see the ongoing dynamism of these wampum agreements in our own times.

The Six Nations Polytechnic (SNP) Partnership Belt that was presented to Niagara College. (Photo credit: Georgia Kirkos)

What’s the Idea: It’s amazing that we can understand these traditions and understandings because they were recorded, rather than being forced to understand them only as historical artifacts.

Daniel: I'm an English professor, and my sense is that if you want to know the literature of Canada and the literature of this place, these would be significant early instances of literacy from our part of the world, rather than thinking that literature comes from, I don't know, Beowulf or something. Beowulf, too, was a wonderful source of literary storytelling, but these wampums house stories and agreements and ceremonies that were maintained here are part of our ancestry, part of our tradition.

What’s the Idea: How’s it been since the book was published?

Daniel: There’s been a lot of events with the books. Just yesterday, I was at my very first “tailgate book launch” at the fairgrounds in Caledonia. People who contributed to the collected volume, Deyohahá:ge, organize the Two Row Paddle on the Grand River every year. Ellie Joseph and Jay Bailey held this book launch at the fairgrounds. We had a hundred or so people there who were paddling and wanting to get to know their Indigenous neighbours, to try to not have what I call “first encounters” forever. We sold out of books, and it was great. We must be getting up to around 20 different events that have been organized around these books, and there's more coming.

Way out in the West Coast, people are interested, too. I'm hoping that they'll continue with that, and I’m hoping I can rise to the occasion. The tricky thing about being a non-Indigenous writer on these things is we don't need more non-Indigenous experts on Indigenous topics. There's lots of Indigenous folks to do that work. So then, the thing is for me to speak clearly for the Canadian side of these agreements. If we have agreements, and only the Indigenous side of those agreements know what they are and pay them any attention, can you really say we have an agreement?

So my challenge, if you want to put it that way, is to get the word out on these things to Canadians, and help Canadians feel like these aren't just Six Nations concepts or Haudenosaunee specialized knowledge. They're here within our own history and they can shape our own way of living into the future. Figuring out how to stay in our sailboat, and to share that river, is the ongoing challenge for all of us.

What’s the Idea: It's not history, it's an active partnership. One of the most important pieces of knowledge to take away from this book is that these treaties and agreements are still in place. It’s important for somebody to understand the Canadian perspective and speak to its place in this agreement.

Daniel: Yeah, it is. And I'm not alone.

What’s the Idea: I moved to Hamilton in my 30s, and it feels like I'm at the beginning of that journey of trying to understand this land. When you go out west, you can feel the presence of the Indigenous people and cultures in everyday life. Those of us in Ontario should acknowledge and understand our history more.

Daniel: I think that's happening. If you think about these books on wampum, why are they appearing now? The Haudenosaunee, Rick Hill, Paul Williams, and others worked hard to repatriate wampum from museums and private collections around the world. They only got them back in the late ’80s and ’90s, up into the 2000s. So, when we say, “How come we didn't know this before?”, part of it is that this knowledge was kept away from people. They were kept away from the Haudenosaunee themselves. They were in vaults of museums and people's collections. It's the percolation of that activism on behalf of the Haudenosaunee and others to get these wampum back into people's hands. Haudenosaunee people have been having meetings with each other, talking over what they know about these wampum traditions, and restoring that knowledge with each other. That's making it possible for people like you and me to learn about them now, these many years later. So, there is a time delay that's been produced, actively produced, as part of that sanctioned ignorance we were talking about earlier. But it's being broken down. We now know more than we did just 10, 15 years ago, and it's a privilege to be part of sharing that news.

What’s the Idea: Thank you so much for writing this book and taking the time to talk with me.

Daniel: Thank you, Matt, I appreciate the chance to talk about this with you.

Grandfather of the Treaties is available from Wolsak & Wynn. It’s also available at your local bookstore; if it’s not in stock, ask them to order a copy for you.

Check out the second part of my conversation with Daniel Coleman, which has more in-depth discussion on the ideas in Grandfather of the Treaties.

The interview was recorded using Google Meet in July 2025.

The transcript was edited by Matt Long of What’s the Idea Professional Editing, with additional copy editing by Anthony Nijssen of APT Editing.