Thinking for the faces about to be born: In conversation with Daniel Coleman on the ideas in his book “Grandfather of the Treaties” (part two)

Daniel Coleman (pictured above) has been on a lifelong journey of understanding the meaning of home and the significance of language. In his latest book, Grandfather of the Treaties, he focuses on those interests in connection with the fundamental original agreements between Europeans and Indigenous Peoples. (Photo credit: Georgia Kirkos)

In part two of the conversation, Daniel Coleman and I discuss some of the many significant concepts in his book Grandfather of the Treaties in greater detail, with a strong focus on the impact of language. This part of the conversation complements the first part of our conversation on the writing of Grandfather of the Treaties.

What’s the Idea: An interesting and important part of the book discusses the often intentional use of language to alter agreements or flip understandings. But it can also happen unintentionally in well-meaning people like yourself, where you could fail to properly convey important knowledge, and that can affect how things or people are perceived, what actions are taken, and so on.

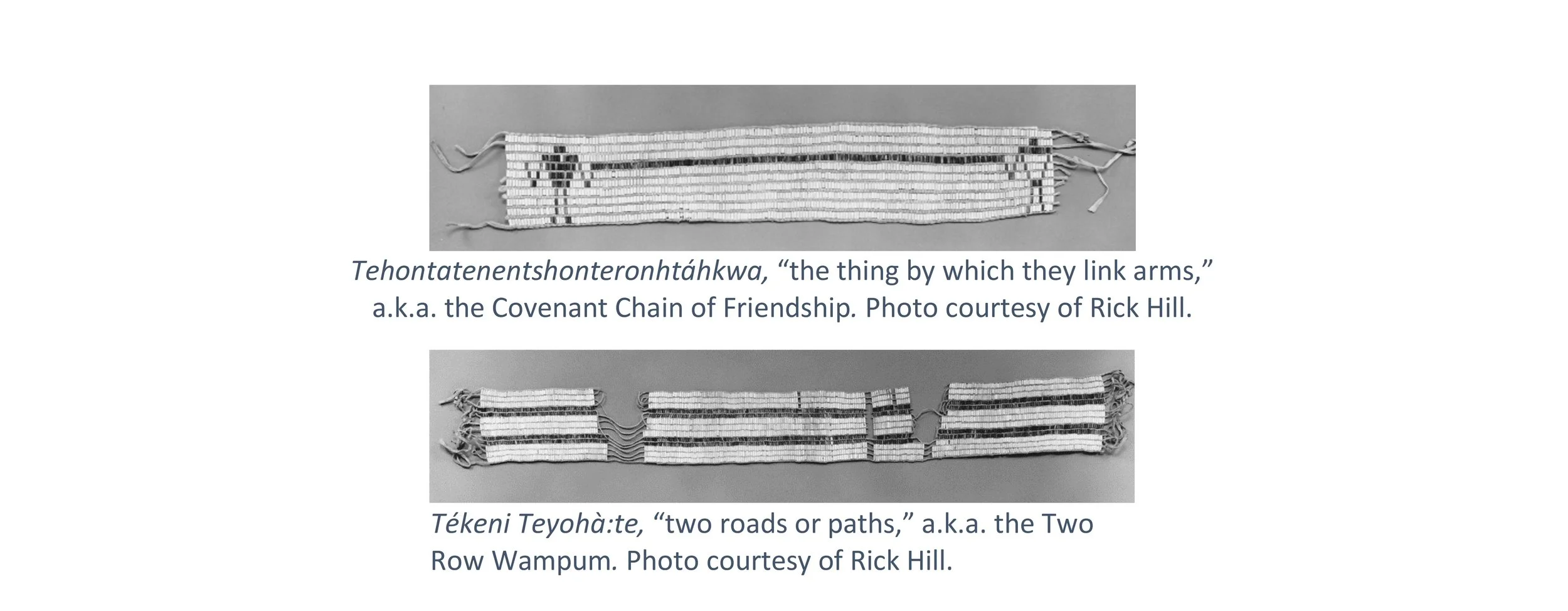

Daniel Coleman: I think you're remembering the section that's on the word “protection”. When you think about these wampum agreements, wampum existed in Haudenosaunee tradition long before Europeans arrived. It was a way to convey the ceremonial understanding of an agreement between different peoples through these iconographically woven bead belts, usually made of purple and white beads. Purple beads are made from quahog shells, and white beads are made from whelk. Haudenosaunee people developed sophisticated traditions for how to keep track of these sophisticated and complex forms of treaty-, agreement-, and ceremony-making without writing. The two that this book is about are the Two Row Wampum and the Covenant Chain, which are different versions of the same kind of agreement.

The Dutch version of it is that the Dutch arrived on the Hudson River and the Mohawk River, right around where Albany is today, in the 1610s. The Haudenosaunee had already had conflict with the French up on the St. Lawrence River, and some of their members were killed by French men up there – Champlain. So they brought this peace-making agreement to the Dutch and said, “This belt represents the River of Life.” It's a long white belt with two parallel rows of purple beads on it. And they said, “It's like we're sharing the river. You sail in a sailboat; we sail in canoes. And these are our traditions, these are how we do things, and it's okay for you to be who you are. Keep your culture and belief and law in your sailing ship, and we'll keep our culture and beliefs and laws in our canoes. But we'll share the river of life.” The whole point was about sharing. And the white rows, or the white beads in between, represented peace, friendship, and respect.

These images (taken by Rick Hill) show the Wampums that served to record the the original established foundational relationships between the Europeans and the Indigenous Peoples of Turtle Island.

The Dutch were reported to have said, “Great, welcome to the family, we'll call you our sons,” and the Haudenosaunee say, “No, no, no, not fathers and sons or parents and children. Let's do it like siblings.” Sisters and brothers were equal. “These rows are equal, and we'll share these things equally. We'll bond together and link arms,” which is the language from the Covenant Chain with the British, which was the version of the same agreement made later on with the British. “We'll link arms with one another, like siblings.” And because of that, the Haudenosaunee allied themselves with the British in conflicts against other Indigenous nations and against the French during the fur trade, and eventually with the British against the Americans when the American Revolution took place. So, that sense of protecting one another's integrity was essential to these wampum agreements.

“The language of these agreements is fascinating to watch over time, to see what they originally meant, and then how they got twisted. ”

I'm using that language of “protection” strategically because the British certainly understood that. They understood that the Haudenosaunee were protecting them from the vagaries of the fur trade, or from allies of the French, in the early days. And later on, they were protecting the British from the Patriots during the Revolutionary War. So, this idea of mutual protection was what the wampum agreements, the idea of alliance, was all about.

You can watch that word get warped over time when you look at the British documents about how they relate to the Haudenosaunee people, to the point where you begin to see the British thinking “protection” meant “we protect you,” like parents protecting their kids. “We” intervened by changing your council system, your governance system, because we are protecting you, we're taking care of you, like parents and kids.

And that really leads all the way into things like the Indian Act and all kinds of other distortions when Canada thought that it had childlike wards rather than equals in Indigenous people. They were no longer seen as allies and friends that held your hand and held you up. That idea of protection became unilateral and patronizing, and it introduced a patriarchal model into relationships that, for Haudenosaunee people, had been organized matrilineally. The language of these agreements is fascinating to watch over time, to see what they originally meant, and then how they got twisted.

What’s the Idea: Part of what strikes me about those original agreements is the generosity of the Indigenous Peoples, as well as the pragmatism. I feel like if it was reversed, it would have been, okay, we'll give you protection for five years, or maybe 50 or 100 if we were generous, and you'd have specific terms, and then we'd see where we were at. It certainly wouldn't be equal or forever. But the Haudenosaunee also acknowledged that Europeans were here and they weren't leaving, so they tried to make it work by sharing wisdom and creating mutually beneficial agreements.

As an analogy, let’s take renters and landlords. You can rent a home your entire life, but no matter what, you don't have a claim to that home, even if you've paid for it the entire time and taken care of it.

Daniel: That’s right. And that's such a good comparison to bring into our minds, somebody renting all that time, taking care of a place, and then having no claim to it. That’s basically a concept of the world as something you share, as compared to private property. When Europeans entered into those treaties and they heard treaty agreements as private property, they were twisting the concept of how to share the place together, because here's the other thing about sharing: It was mutual protection between the British, let's say, and the Haudenosaunee, but it was also protection of the river. There was this sense that it's not property; it's a living being. It's a participant in the treaty ceremony itself. And so, there's a deep ecological awareness that is just part of Haudenosaunee philosophy. That wasn't readily available in British thinking in that period of the Enlightenment and industrialization. You can see land being shared or land being owned as being very different concepts of things. And that difference brings us all the way up to the relevance of these wampum agreements to the present.

You know, gradually, slowly, belatedly, our Western culture is beginning to realize we treated this place like it was a dead thing and a property. And now, you know, that death toll is starting to ring, whether it's wildfires or polluted water, or the lack of food-growing land, or all kinds of things. We're beginning to realize the harm of that way of thinking.

The notions that were embedded with those agreements, as you said, weren't for five years, because five years has no concept for a land. A land is formed. Its nutrients and its plant-based growth and decline and composting and all that process takes centuries. So when they were talking about sharing the river, they were talking about as long as the river flows, as long as the sun shines, as long as the grass grows. That's how long these treaties were supposed to last.

There's a really fascinating phrase in the oral narrative of the Two Row Wampum. They said “nobody can claim this land except the faces waiting in the ground to be born,” or the faces rising to be born from that earth. And you think, well, what does that mean? Well, faces are like the lives, the seeds, the embryos of new life that are waiting in the earth to be born. That's who can have the rights to these treaties, to these agreements, to this protection. That's who it's aimed at.

Well, that's a very different view than saying as long as the shareholders are still paying the company, or, you know, as long as we have the Conservatives or the Liberals in power, or whatever it is. It's a very biome-based way of thinking about what is peace, what is a treaty? What are agreements between people for? Those deep ecological sensibilities are woven into these treaties.

Burlington Bay on a September evening in 2025, taken from Bayfront Park in Hamilton, Ontario. (Photo credit: Matt Long)

What’s the Idea: The relations within our country — not to mention the rest of the world — are in a state of tension and confusion, in my opinion. In this book, we go right back to the beginning with these first agreements and try to understand the original ideas and intentions of those first binding agreements. Now as I look forward and try to understand what could be done, this book presents the idea that the answers are there.

Sometimes as a Canadian, I hear about Land Back and I’ve wondered what that means for me. My mom’s side has been here for a long, undetermined amount of time, but my dad was the first generation born here from Irish immigrants. Is Canada supposed to be dissolved and I then return to Europe? This book says no, that wasn't the idea. We settlers and Indigenous people can both coexist.

Daniel: Our ancestors arrived with the concept of private property, and so it's easy for us to think, well, if we're supposed to give the land back, then we should somehow go home, wherever that may be. Back to Ireland, in your case. But when you don't understand the land that way, you can then understand land as a place that takes care of us, that nurtures us, that's like mother. To us, that's why you would say Mother Earth. Lee Maracle, a Stó꞉lō thinker who passed away a few years ago, puts it this way in her book My Conversations With Canadians: “Many people think that the colonialists should just go home. I don't think they should do that. I think they should learn to love the land like I do.”

And, you know, we have chances to do that. You think about the recent election we had in Canada, where people were afraid that we were going to become the 51st state, and they decided they wanted to have their “elbows up” to protect Canada. Well, what was that? There was a sense of wanting to love the place where they live.

But then we get the confusion. If that love of place where we live is filtered through the concepts of private property and dead land that you can extract resources from, then you get Bill C-5, and you get Bill 5, and these laws that are overriding treaty rights and are going to obliterate environmental regulations to extract minerals. You think, is that loving the place? Is that what we're trying to protect?

If we want a future here, and we don't want to become the 51st state. How do we do that? It seems to me that the Two Row and the Covenant Chain give us really good models for making alliances with one another and sharing the land, not so that we can take what we want from it forever, but so that we can live here forever, so that it will last forever, and we can have healthy generations to come.

I think this is a critical moment in Canadian political and environmental life. It'll be interesting to see what this new government does. Right now, they're in the thick of negotiating with First Nations about these desires to create a new energy pipeline, to extract minerals, and so on. It's going to be interesting to see how much of a mutual sharing, caring – caring for one another and for the place, literally – that will be in their new policies. We've made lots of mistakes before, we could make some more. But let's hope that we see some different ways of carrying and sharing for the river on which we live.

What’s the Idea: Is there anything that you are specifically watching for?

Daniel: In the Land Back sections of the book, I talk about the importance of being guided by Indigenous understandings of what land is and how land works. And so, I called for Indigenous governance. I don’t mean that we need an Indigenous government, although that might be good too! But we need to be guided by those principles of “the faces waiting in the ground to be born.” And so far, the nation states of Canada, the United States, everywhere else, have been so much based on extraction of private resources from private property — or from public property, too — that we don't consider the faces in the ground waiting to be born. We need people who have a long experience of living that way to guide our public policies, environmental policies, the ways we create energy for the future, all kinds of things. These wampum agreements from long ago give us guidance for today, not just for 400 years ago.

What’s the Idea: The concept of making decisions for seven generations is one of those significant ideas that changes your way of thinking when you can wrap your head around it. We need to make decisions that respect the needs of the people not yet born.

“Language carries deep philosophical understandings that are kind of invisible until you encounter a different language.”

Daniel: We live in a very blessed time in the sense that there's a whole generation of Indigenous thinkers who've learned from the old traditions and the elders, but who are also highly educated in the Western academy and can speak these things into our current cultural life in powerful, convincing, and sophisticated ways.

I'm very conscious of publishing these books in the midst of 15, 20 books by Haudenosaunee scholars that have been published in the last 15 years, just helping us understand these traditions and their currency with us in the present. There's expertise around, if you want to put it that way, and a very sophisticated generation of young Indigenous leaders who can speak to the times we're in. So, we're really fortunate. It's not like there's no resources, or ways of thinking, or influential people, or sophisticated ideas to work with. The books that I've edited and written only exist because that work has been done by Haudenosaunee writers and thinkers, and because I got to meet people like that, both on the reserve and at the university.

What’s the Idea: The part of the book where you write about the concept of the word “we” is very singularly understood by Europeans, yet there are at least four different ways of understanding “we” in Haudenosaunee language, was so interesting. I feel like that’s significant for decision-making in the present, especially in combination with the future faces in the ground. If we’re thinking about the lives that will exist in the future, and if we’re including them in the equation, it should significantly change decision-making.

Daniel: Language carries deep philosophical understandings that are kind of invisible until you encounter a different language. I took an introductory Mohawk language class, and was fascinated with learning about pronouns. In the Mohawk language, they have dualic inclusives and dualic exclusives, and pluralic inclusives and pluralic exclusives. That's just saying that they have very refined concepts of pronouns, meaning that you can say words like “we” to mean you and I are talking, but not somebody else. You can convey that with one pronoun, and then you can also say “we”, but it includes somebody who overheard our conversation or is there around us, and there’s a pronoun that can carry that. In other words, it doesn't assume that “we” means just everybody. In their language, I couldn’t say “we” for all Canadians, like what is meant by the phrase “the royal we.” Pronouns in Mohawk are much more relationally alert than they are in English.

A different example is the words for relatives. The words for relatives in Mohawk are verbs rather than nouns. So, let's say Grandma. Somebody isn't just our grandma. They do grandmothering. It's a verb, so a person who's older grandmothers. People who are younger receive grandmothering from somebody who's older. That’s not just a static concept of grandma and grandkids. That's an action, and an initiation of action and a receiving of action.

Relationships are actions, they're how we treat one another. Mohawk language conveys that. So when we talk about Mother Earth, that's the activity of Earth taking care of us, and we can receive that care or not. We can be like rebel kids and say, “I'm not doing that,” or “I don't want to receive what Earth gives,” or “I'm going to abuse what Earth gives.” I think when we hear Indigenous folks say “Mother Earth,” we hear it through the noun consciousness of English and tend to think, oh, that's kind of like an anthropomorphic concept. We're making Earth into a human being instead of seeing it’s a way of understanding what Earth is doing for us, that Earth nurtures us. It mothers us. We hope that Mother Earth will keep mothering us if we interact with her in responsive and grateful ways.

One of Coleman’s goals is to bring a greater understanding of how to build from these established relationships, “rather than starting from scratch all the time.” (Photo credit: Geoff Skirrow)

The written text of a treaty written in English, and made into law for Canadians, is going to miss so much of what people are actually talking about in that treaty moment because of the nature of English and the nature of translation into the written form. We say it's written in stone, as if it's a dead thing. Wampum is not alphabet writing. It only lives when you pick it up and talk about it. It's an oral form, and it reminds you of what it is, but people speak of the beads themselves conveying the spirit of the meaning in the words.

Among the people who make wampum beads out of the shells of quahog and whelk mollusks on the east coast are the Shinnecock people. In an essay in the Deyohahá:ge collection, Kelsey Leonard, who's from that region, talks about the word that they use for those beads, and it's wanaumwash, which means “truth-teller.” And you say, well, why is a bead the word for a truth-teller? And that's because crustaceans, shellfish, live by filtering water through their bodies. If you want to know the truth of what's in the water, look in their body, it's right there. If you are saying there's no pollution here, check the shellfish. They'll know if it's true or not.

What’s the Idea: We'd be remiss to not mention “the myth of first encounter,” the repeated ignorance of Europeans meeting Indigenous peoples. There is so much that we seem to refuse to learn. Even something as important as these wampum agreements aren’t known by everyone.

Daniel: Thanks for bringing up the myth of first encounter. That comes from the work of Alice Te Punga Somerville, who is Maori. Alice talks about the myths that keep colonialism in place. One of them is terra nullius, the idea that the land was empty. And then the second one is the myth of first encounter, and what she means by that is that people in colonial society have a kind of built-in forgetting that says, oh, we don't remember that we met you people before. Every meeting seems like it's the first time, and we don't seem to learn anything from having met before.

It's part of the, you could say, “sanctioned ignorance” that's part of our way of being educated as Canadian people. There's a sanctioning of certain kinds of ignorance. Wampum traditions are one really good example, but there's so many. We live half an hour from Six Nations here in Hamilton, and the majority of Hamiltonians don't even know that, let alone that there's a long history of Six Nations being in this region. The reason Mohawk Road in our city is called Mohawk Road is that it used to be the Mohawk Path following along the top of the escarpment the whole length of Lake Ontario. This place is full of Indigenous story and tradition.

You look over Cootes Paradise, that is a Dish With One Spoon. Now, because of land acknowledgements, people begin to hear these words a little bit. But until recently, it was like first encounter every time. We had no idea that there was a history, that there was a set of relationships that had already been built, that there are already ways of creating better relations than what we've been living with. So, part of the effort of these books is to get us to the second and third and fourth encounter, and the 28th encounter, so that we can build from some of these relationships, rather than starting from scratch all the time.

What’s the Idea: I hope people put the work in to do that. It feels, at least to me, like a very fundamental task as a Canadian.

Grandfather of the Treaties is available directly from Wolsak & Wynn. It’s also available at your local bookstore; if it’s not in stock, ask them to order a copy for you.

My conversation with Daniel Coleman about writing Grandfather of the Treaties is also available in part one of this interview.

Check out this article from Open Book that has an excerpt from Grandfather of the Treaties.

Here’s an important article about Lee Maracle called “Lee Maracle, My Conversations With Canadians.”

The interview was recorded using Google Zoom in July 2025.

The transcript was edited by Matt Long of What’s the Idea Professional Editing, with additional copy editing by Anthony Nijssen of APT Editing.